Improvements on Stirling’s Approximation using Taylor Series Expansions

2025-04-20

Introduction

Stirling’s Approximation is a well-known approximation to the factorial. n!\sim \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\sqrt{2\pi n} This approximation is quite good for sufficiently large n. For n=100, the approximation only has a 0.08 \% error.

However, we must ask – can this approximation be improved upon? Stirling’s Approximation has a convenient expression – simple, not painful to plug into a calculator. But can we find an uglier solution that yields a better approximation? The answer – yes, with special emphasis on the word "uglier"

The First Series Expansion

Let’s start with what we know – how to derive Stirling’s Approximation. The path to an improvement will make itself quite obvious midway through the derivation.

We know that n!=\Gamma(n+1)=\int_{0}^{\infty}x^ne^{-x}\,dx A path towards an approximation makes itself obvious to us. If we want to approximate n! all we have to do is approximate \Gamma(n+1). And if we want to approximate \Gamma(n+1), all we have to do is approximate x^ne^{-x}

Let’s rewrite that integrand as

x^ne^{-x}=e^{n\ln{x}-x}

Let’s play around with introducing a new variable y=x-n

Then we have n\ln{x}-x=n\ln(y+n)-y-n=n\ln\biggl[n\biggl(1+\frac{y}{n}\biggr)\biggr]-y-n n\ln{x}-x=n\ln{n}+n\ln\biggl(1+\frac{y}{n}\biggr)-y-n

Now think about the fraction \frac{y}{n} \frac{y}{n}=\frac{x-n}{n}

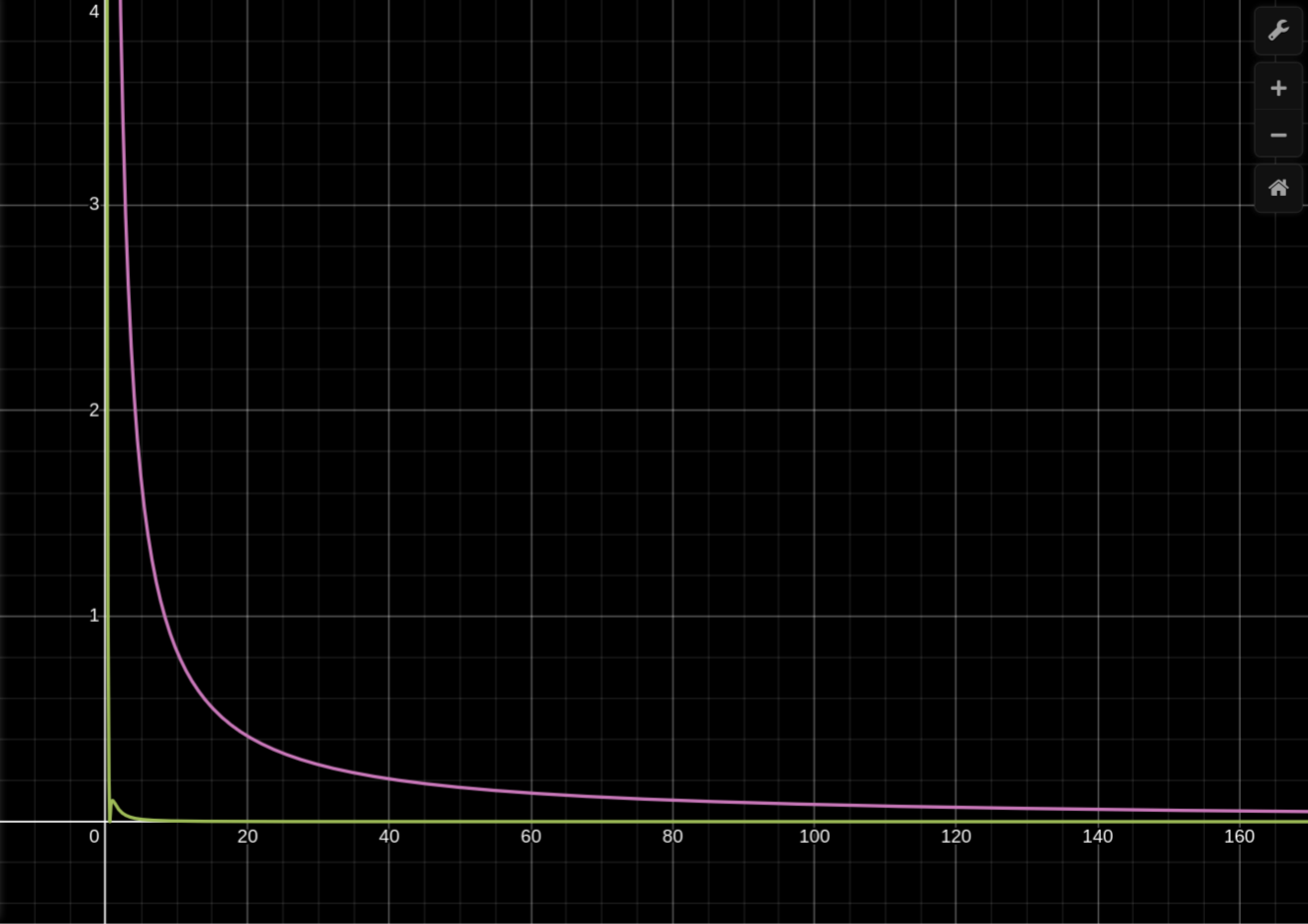

Now consider a few things. The graph of x^ne^{-x} has a sharp peak at x=n (proof left as an exercise for the reader, just set the derivative to zero)

Near the peak at x=n, we must have x-n near zero.

Far away from x=n, x^ne^{-x} takes on small, negligible values – the larger n is, the sharper the peak and the more irrelevant are the terms far from the peak.

So if we only consider terms near the peak (valid for large n), then \frac{y}{n}=\frac{x-n}{n}\approx 0

But wait, we have \ln\bigl(1+\frac{y}{n}\bigr)

We know that the Maclaurin series expansion for \ln(1+x) converges for |x|<1 so, given that |\frac{y}{n}|\approx 0, we can use the Maclaurin series expansion for the logarithm!

Also note that, for very small x, we can keep just the first few terms from the \ln(1+x) expansion and have a small error. As x gets larger, the error from the truncated Maclaurin series grows.

Since \frac{y}{n} is very small here, we can use the truncated Maclaurin series with a very small error, the error getting smaller with larger n.

So we then have

n\ln{x}-x=n\ln{n}+n\Biggl[\biggl(\frac{y}{n}\biggr)-\frac{1}{2}\biggl(\frac{y}{n}\biggr)^2+\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^k}\Biggr]-y-n n\ln{x}-x=n\ln{n}+y-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\Biggl(\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^{k-1}}\Biggr)-y-n n\ln{x}-x=n\ln{n}-n-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\Biggl(\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^{k-1}}\Biggr)

Amazing! Now let’s plug all of this back into our integral for the gamma function.

\Gamma(n+1)=\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{n\ln{x}-x}\,dx

Whoops, our expression for n\ln{x}-x is in terms of y and our integral is dealing with x Easily fixed – let y=x-n so that \,dx=\,dy

The bounds of integration change from (0,\infty) to (-n,\infty)

\Gamma(n+1)=\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(n\ln{n}-n-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^{k-1}}\Biggr)\,dy

Using e^{a+b}=e^ae^b we find

\Gamma(n+1)=\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp(n\ln{n}-n)\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^{k-1}}\Biggr)\,dy

Note that e^{n\ln{n}-n}=e^{n\ln{n}}e^{-n}=n^ne^{-n}=\bigl(\frac{n}{e}\bigr)^n

\Gamma(n+1)=\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\sum_{k\ge 3}(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^k}{kn^{k-1}}\Biggr)\,dy =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\ldots\Biggr)\,dy

Now recall the earlier argument about a truncated series having low error since \frac{y}{n}\approx 0 near the integrand’s peak. This seems like a good point to use that truncated series – but how many of the terms do we keep?

Let’s set a definite goal. Suppose we want an error that is O(n^{n-3/2}) How many terms should we keep to achieve that? I’ll give the details later, but in this case, we only need to keep the first three terms for our desired accuracy.

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\Biggr)\,dy

Let’s pull the first term out to get

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\Biggr)\exp\Biggl(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\Biggr)\,dy

Also, to make our life easier, let’s mess with the bounds of integration a bit here. When working in terms of x, our integrand’s peak was at x=n Now that we are working with y=x-n our integrand’s peak should be at y=-n

For very large n, the peak will be very sharp so terms to the left of the peak will be negligible. Thus, we can change (-n,\infty) to (-\infty,\infty) and incur very little error.

So we have

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\Biggr)\exp\Biggl(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\Biggr)\,dy

The attentive reader will realize that this section’s title of "The First Series Expansion" implies that we will use another series expansion – any guesses what we’re gonna use now?

The Second Series Expansion

To anyone who predicted we would now use the Taylor series for e^x – yes, you guessed right.

Let’s expand out

\exp\Biggl(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\Biggr)=\Biggl(1+\biggl[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\biggr]+\frac{1}{2}\biggl[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\biggr]^2+\ldots\Biggr) If we want an error that is O(n^{n-3/2}) , we can drop terms of order y^8 and onwards – I will prove this later. So we find that \exp\Biggl(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}\Biggr)\approx \Biggl(1+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\frac{y^6}{18n^4}-\frac{y^7}{12n^5}\Biggr)

Then we have

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\Biggr)\Biggl(1+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\frac{y^6}{18n^4}-\frac{y^7}{12n^5}\Biggr)\,dy

Let us now introduce

I_k=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\biggl(-\frac{x^2}{2n}\biggr)x^k\,dx

If k is odd, the integrand becomes an odd function because \exp\biggl(-\frac{(-(2m+1))^2}{2n}\biggr)(-x)^{2m+1}=-\exp\biggl(-\frac{(2m+1)^2}{2n}\biggr)x^{2m+1}

Since the bounds of integration run from -\infty to \infty the integral must then equal zero when k is odd. So we can consider only the case where k is even i.e.

I_{2m}=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\biggl(-\frac{x^2}{2n}\biggr)x^{2m}\,dx

Let u=\frac{x}{\sqrt{2n}} so that \,dx=\sqrt{2n}\,du

Then we have

I_{2m}=\sqrt{2n}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-u^2}\left(u\sqrt{2n}\right)^{2m}\,du=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-u^2}u^{2m}\,du

Rename u to x and we have

I_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}x^{2m}\,dx

Integrate by parts using u=e^{-x^2} and \,dv=x^{2m} \,du=-2xe^{-x^2} v=\frac{x^{2m+1}}{2m+1}

I_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\left(\left.e^{-x^2}\frac{x^{2m+1}}{2m+1}\right\rvert_{-\infty}^{\infty}+\frac{2}{2m+1}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}x^{2m+2}\,dx\right) =(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\left(\frac{2}{2m+1}\right)\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}x^{2(m+1)}\,dx

Let

Q_{2m}=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}x^{2m}\,dx

Then, from our formula for I_{2m} that we had just before integration by parts,

I_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}Q_{2m}

But we also know that

I_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\left(\frac{2}{2m+1}\right)Q_{2(m+1)}

This tells us that

Q_{2m}=\left(\frac{2}{2m+1}\right)Q_{2(m+1)}

Q_{2(m+1)}=\left(\frac{2m+1}{2}\right)Q_{2m} Q_{2m}=Q_{2(m-1+1)}=\left(\frac{2(m-1)+1}{2}\right)Q_{2(m-1)}=\left(\frac{2m-1}{2}\right)Q_{2(m-1)}

We know that Q_{0}=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}\,dx=\sqrt{\pi}

So now we can solve for Q_{2m} in the way we would solve any recurrence relation

Q_{2m}=\left(\frac{2m-1}{2}\right)Q_{2(m-1)}=\left(\frac{2m-1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{2m-3}{2}\right)Q_{2(m-2)} =\left(\frac{2m-1}{2}\right)\left(\frac{2m-3}{2}\right)\cdots\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)Q_0 =\frac{1}{2^m}\left(\prod_{i=1}^{m-1}(2i+1)\right)\sqrt{\pi}

Note that

\prod_{i=1}^{m-1}(2i+1)=\frac{1\cdot 2\cdots (2m-1) \cdot 2m}{2\cdot 4 \cdots(2m-2) \cdot 2m}=\frac{(2m)!}{\prod_{i=1}^{m}(2i)}i=\frac{(2m)!}{2^mm!}

Thus we have

Q_{2m}=\frac{1}{2^m}\left(\frac{(2m)!}{2^mm!}\right)\sqrt{\pi}=\frac{(2m)!}{2^m\cdot 2^mm!}\sqrt{\pi}=\frac{(2m)!\sqrt{\pi}}{2^{2m}m!}

I_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}Q_{2m}=(2n)^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\frac{(2m)!\sqrt{\pi}}{2^{2m}m!}=n^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\frac{(2m)!\sqrt{\pi}}{2^{m-\frac{1}{2}}m!}

Now let’s return to our expression for the factorial. Note that we drop all terms of the form I_{2k+1} since they equal zero.

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\Biggr)\Biggl(1+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\frac{y^6}{18n^4}-\frac{y^7}{12n^5}\Biggr)\,dy =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\Biggl(I_{0}+\frac{I_3}{3n^2}-\frac{I_4}{4n^3}+\frac{I_6}{18n^4}-\frac{I_7}{12n^5}\Biggr) =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\Biggl(I_{0}-\frac{I_4}{4n^3}+\frac{I_6}{18n^4}\Biggr) =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\Biggl(\sqrt{2\pi n}-\frac{24n^{5/2}\sqrt{2\pi}}{32n^3}+\frac{720n^{7/2}\sqrt{2\pi}}{864n^4}\Biggr) =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\sqrt{2\pi n}\Biggl(1+\frac{1}{12n}\Biggr)

Remembering that we chose terms so that we have an error of O(n^{n-3/2}) we can write \Gamma(n+1)=\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\sqrt{2\pi n}\Biggl(1+\frac{1}{12n}+O\left(\frac{1}{n^2}\right)\Biggr)

Let’s see how much of an improvement this is.

Knowing which terms to keep

Earlier I promised to explain why I dropped the terms I dropped – here you go.

Let’s look at the first place where we dropped terms.

\Gamma(n+1)=\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}+\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\ldots\Biggr)\,dy =\biggl(\frac{n}{e}\biggr)^n\int_{-n}^{\infty}\exp\Biggl(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\Biggr)\exp\Biggl(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\ldots\Biggr)\,dy

Suppose we want an error that is O(n^{n-\alpha/2}) Consider the k’th term in the second exponential,

(-1)^{k+1}\frac{y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}

Now suppose we keep all terms up to the k’th term and Taylor expand. We will get

1+\left[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right]+\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right]^2+\ldots

Suppose we keep all the terms in this expansion up to the j’th term. The j’th term in this second series expansion is \frac{1}{j!}\left[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right]^j \sim \left[\frac{y^3}{n^2}+\ldots+\frac{y^{k+2}}{n^{k+1}}\right]^j Remember we wanted an error of O(n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}})

Now we want to choose j such that there is AT LEAST one term within the larger j’th term whose contribution to the approximation is of an order greater than n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}}

Note that there can be unnecessary terms within that j’th term – those can be dropped. But so long as there is even one necessary term, we want to consider the whole j’th term and then remove specific "sub-terms" as needed.

The term with largest-order contribution in that j’th term is going to be \sim \frac{y^{3j}}{n^{2j}} Using our earlier formula for I_k, we see that the contribution will be of order \sim n^{n-2j+\frac{1+3j}{2}}=n^{n-\frac{j-1}{2}}

We want this order to be greater than n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}}

The order increases/decreases in integer increments, so the smallest order greater than n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}} is n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}+1}=n^{n-\frac{\alpha-2}{2}}

So we want the order of that contribution to be greater than or equal to this MINIMUM order of contribution for the term to be relevant

i.e.

n-\frac{j-1}{2}\ge n-\frac{\alpha-2}{2} j-1\le\alpha-2 j\le\alpha-1

This inequality tells us that, for any j<\alpha+1, there will be AT LEAST one term we want to keep within that larger j’th term. We want to collect all the terms with some relevant contribution, so we take the largest possible j that has a term we want.

j=\alpha-1

Now for k we similarly want to set k to be as high as we can get it without missing any important terms. We need AT LEAST one important term added by setting k to whatever value it is. The term with highest-order contribution corresponding to changes in k comes from the first term in the exp-series expansion (refer back to the start of this section if confused)

\sim \frac{y^{k+2}}{n^{k+1}}

If even just this term is relevant, we have justification for setting k to include this term.

The contribution from this term is of order \sim n^{n-(k+1)+\frac{1+(k+2)}{2}} = n^{n-\frac{k-1}{2}}

We want the order of that contribution to be at least n^{n-\frac{\alpha-2}{2}}

n-\frac{k-1}{2}\ge n-\frac{\alpha-2}{2} k-1\le \alpha -2 k\le \alpha-1

This tells us that for all k\le \alpha-1 we will have AT LEAST one term we need to keep. We take the largest k value permitted by this inequality, giving us all the terms needed as a result.

k=\alpha-1

So if we want an error in our approximation that is O(n^{n-\frac{\alpha}{2}}) then we can drop terms in our series expansions as follows

We let k=\alpha-1 j=\alpha-1

In our integral for the gamma function, we will keep the terms in the second exponential up to the k’th term, i.e. approximate as

\Gamma(n+1) \approx \left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^n\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\exp\left(-\frac{y^2}{2n}\right)\exp\left(\frac{y^3}{3n^2}-\frac{y^4}{4n^3}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right)\,dy

And then when we Taylor-expand the second exponential in that integral, we truncate the series in this manner 1+\left[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right]+\ldots+\frac{1}{j!}\left[\frac{y^3}{3n^2}+\ldots+\frac{(-1)^{k+1}y^{k+2}}{(k+2)n^{k+1}}\right]^j

When we substitute that series expansion back into our integral, we will have an approximation of the form

\Gamma(n+1)\approx \left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^n\sum_{m}\frac{I_{2m}}{n^{s_i}}

Where we have

I_{2m}=n^{m+\frac{1}{2}}\frac{(2m)!\sqrt{\pi}}{2^{m-\frac{1}{2}}m!}

This gives us a way to improve on the Stirling Approximation to any desired accuracy. The result quickly gets ugly for increasing accuracy. However, if you’re willing to tolerate the ugliness, the increased accuracy is quite satisfying to have.

Conclusion

Hopefully you enjoyed this post. I have not written anything in a long time because of a combination of factors – I’ve been busy with lots of different things, I had a bit of anxiety about the quality of my writing, and the reasons go on and on. I’m hoping to write more in the next few months, however, and build this habit again. I have some nice ideas about stuff to write about, so expect some interesting content.

If I made any errors here or if you have any suggestions to make, please contact me at my discord floofydoggo or my email address chancellorceti@gmail.com

I would also like to give credit to Daniel Schroeder’s textbook "An Introduction to Thermal Physics" that showed me this proof of Stirling’s Theorem for the first time and got this question into my head. Amazing textbook, I learnt quite a bit from it.

I hope to return with more interesting stuff soon. Thanks for reading!